Less than three weeks from the anniversary of the Rana Plaza disaster (and with the compensation fund still short of money needed for medical bills), this is my first refashion for TRAID’s #SewSolidarity Challenge. I’ve got a skirt to show, and I’ve also got quite a bit to say. I’d recommend you grab a tea, and perhaps a biscuit, before you begin…

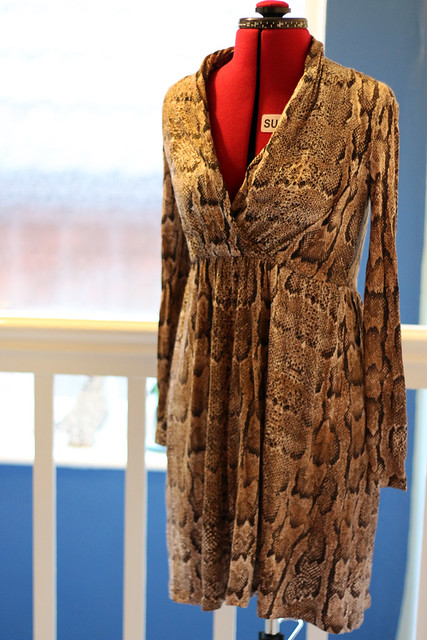

This fabric started off as a dress, which I purchased second-hand in a charity shop. The original dress was too small for me, but that was fine as I wanted to use it for fabric.

All I learnt about how the dress was made from the tag, was that it was a H&M product (H&M were one of the companies who sourced from Rana Plaza), and was ‘made’ in Cambodia. Our clothes (and our textiles) aren’t made by machines, they’re made by people. That ‘made in’ label told me that the ‘cut, make, and trim’ stage of this dresses’ lifecycle (from cutting the fabric to finishing the dress) took place in Cambodia, probably in a garment factory. Given that garment factories typically employ a production line approach for speed, the dress was probably made by a number of people; each focused on sewing a small section of the dress. The majority of garment workers are women, so I can assume the original dress was made by a number of Cambodian women.

I took the dress apart, unpicking the original stitches made by garment workers in Cambodia, and used the fabric to make a Marilla Walker Ilsley Skirt. I used almost all of the dress to construct this skirt, with just a few small pieces going into my scraps bin. I spent a lot longer on the Ilsley Skirt than the original garment workers would have had to construct the dress – I hand-stitched the hem while sat watching a movie.

What the tag in the dress didn’t tell me, was what other countries, and people, were involved in the creation of the original dress. The ‘cut, make, and trim’ stage only represents a tiny proportion of the overall process involved in creating a textile – from cotton boll, or sheep’s fleece, or oil – and transforming that textile into an item of clothing. That wider process involves huge amounts of resources (water, chemicals, electricity, etc.), huge numbers of people (approximately 40 million people worldwide in garment construction), and huge numbers of animals (for silk, wool, leather, fur, skins).

As sewists and crafters, I think we are more aware of the time and labour involved in the production of a garment. As sewists, we’ll feel particular pain at the ‘virtual factory standard’ that companies have used to define the target times for garment workers to produce clothing. You think the time allowed on GBSB is bad, try 15 minutes to produce a pair of five-pocket jeans.

I also think as crafters we become more aware of the processes that underpin our hobbies, because once you become involved with a craft you start thinking about how you can get involved at earlier stages of the production process. So knitters often become spinners, and knitters and sewists become dyers and fabric designers. I think this thought process – this interest in how something is made, from beginning to end – is vital. We need to be more conscious about what it is we are buying – where it was made, who by and how.

That’s because, currently, the processes used to produce garments – and textiles – have a hugely detrimental impact on people and the environment. This isn’t anything new – cotton production traditionally was underpinned by slavery – but globalisation, fast fashion, and the pressure for ever cheaper prices have increased the scale of production – and the associated risks. Those risks are numerous, including the effect of particles during cotton / fibre production and preparation on the respiratory system, if inadequate protection is provided, or the impact of chemicals used in textile production and dyeing on workers within factories that don’t provide adequate protection, and on the surrounding environment and population if those chemicals are not adequately disposed of and are instead allowed to pollute waterways and the air. There is also the impact on the health of garment workers of working long hours without earning a living wage, possibly in unsafe conditions. Rana Plaza wasn’t an isolated incident, many garment workers have been killed or injured at work; fires are particularly common.

Managing the textile/garment production process, and its associated risks, ethically requires investment and commitment from clothing – and textile – companies. However, the drive to produce huge volumes of textiles and garments quickly and cheaply has led to production systems where companies outsource to middlemen huge portions of the production process. In this way, companies have outsourced a lot of production risks, and costs. They’ve also outsourced a lot of the control, and visibility, of these processes. And they’ve done so in countries where workers, animals, and the environment are subject to much less protection.

Like many sewists, I buy limited RTW clothes, but I don’t think that makes these issues any less relevant to me, given the huge global impact of these processes. Also, I do buy a lot of fabric – and many of the same issues apply to fabric production.

Each year, the Uzbekistan government transports approximately a million of it’s own citizens, including children, from their homes to serve as forced labour, picking cotton for two months during harvest time (read more here). These people are given mandatory quotas to meet and are punished or fined if they fail to meet them. As a shopper, it isn’t easy to tell if the bolls used to create a bolt of cotton originally came from Uzbekistan, but, if so, forced child labours probably picked those bolls.

Poorly regulated factories processing and dyeing fabrics are also hugely problematic. Not only for staff provided with inadequate protection from fibres and chemicals, but also for surrounding populations. Treating the water used in dyeing to remove chemicals has a cost associated with it, so factories regularly pump untreated water into waterways. This is a huge issue in India and in China, with 1 in 4 of China’s population drinking contaminated water daily. There have been multiple incidents of rivers taking on the colour of a dye from a nearby factory, including the Caledon river being dyed indigo.

We’ve all become spoilt by cheap prices, and accustomed to spending less but buying more, but the prices are false. It isn’t possible to produce a t-shirt for £3, or a pair of jeans for £6, or probably a metre of fabric for £1, if all aspects of the production process have been managed sustainably and responsibly. Obviously a high price isn’t a guarantee that something has been produced ethically, but I’m adjusting what I expect to pay so that I don’t see £5 for a ball of wool or £10-20 for a metre of fabric as ‘expensive’.

Obviously it isn’t easy when you pick up an item of clothing, or a bolt of fabric, to know how it was produced, but from now on I’m going to at least consider those questions, and think about the resources, people and animals involved.

Otherwise we’re validating those clothing companies who have excused their own practices by stating that consumers don’t care how their products are manufactured.

All facts referred to are courtesy of ‘To Die For: Is Fashion Wearing Out the World?’ by Lucy Siegle, which I’d hugely recommend.