This is the first in a blog series I’m planning exploring the history of textile and related industries in British cities. It’s something I enjoy researching, and I hope you’ll enjoy the blog series. For this first post, I’m writing about my home city, Birmingham. If you can add anything to the info below, do get in touch.

Introduction

Birmingham has been a market town since 1166, when the local Lord, Peter de Birmingham, was granted a royal charter by Henry II to hold a weekly market. By the 14th century, Birmingham appears to have had an establish trade in wool, textiles, and leather working.

Key industries explored in more detail below are leather, button-making, and thimbles. However, Birmingham has had a wider impact on textile industries not explored in detail, such as the 1732 invention, by Lewis Paul and John Wyatt of Birmingham, of roller spinning (a process of spinning cotton into yarn or thread using machinery), and their opening in 1741 of the world’s first cotton mill in Birmingham’s Upper Priory.

Tanning & Leather

Tanning was one of Birmingham’s first industries in the 14th century. By the 16th century there were at least a dozen tanners operating in Birmingham, and a dedicated leather hall where business was transacted. Evidence of the tanning industry has been found during excavations, with clay and timber lined pits discovered in the city centre at Edgbaston Street, Park Street and Floodgate Street. The pits would have stored lime used to remove hair and fat from hide, or water and tannin for preservation. The Birmingham tanning industry was in decline by the early 19th century, with the leather hall removed and trade restricted to the making of bellows and harnesses.

NOW: P&Co have a selection of Leather Goods currently produced in Birmingham. The following video shows these being made:

Buckles and Buttons

Birmingham specialised in the production of small items (hinges, buttons, buckles, hooks, etc.) in a range of materials including metal and glass, which were collectively known in the 18th century as “toys”.

Matthew Boulton, an entrepreneur in the toy industry, described the Birmingham buckle trade to a House of Commons select committee in 1760, estimating that it employed at least 8,000, and generated £300,000 worth of business, with the majority of stock destined for export to Europe.

The buckle trade collapsed in the 18th century as a result of people starting to wear slippers or shoes fastened with strings. In 1791, bucklemakers petitioned the Prince of Wales on behalf of the 20,000 bucklemakers in distress, and the Prince of Wales and Duke of York responded by ordering their own entourage to wear buckles. Further petitions were submitted in 1792 and 1800, and bucklemakers are rumoured to have paraded a donkey, its hooves adorned with laces, to insult wearers of the new fashion.

Although the market for buckles didn’t revive, the button trade flourished in Birmingham in its place. “It would be no easy task”, William Hutton wrote in 1780, “to enumerate the infinite diversity of buttons manufactured here”. In the 1800s there were over one hundred button makers based in the Midlands.

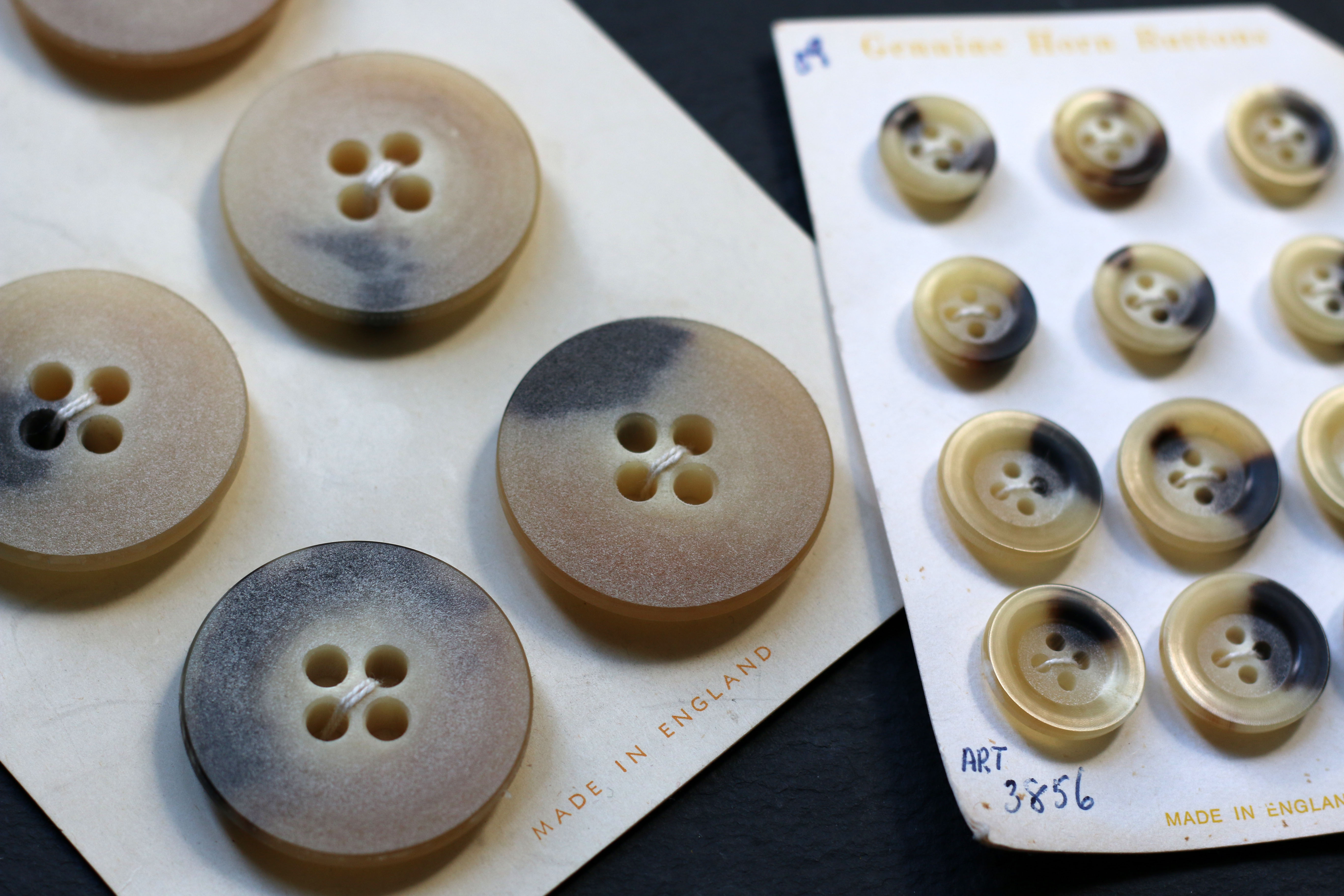

Originally, the button was a by-product of the slaughter-house, with buttons produced from animal hoof and horn. The raw hoof and horn had to be heated and moulded, and then turned and polished by hand. However, the Birmingham button trade was diverse including pearl, shell, metal, cloth-covered, and later plastic, buttons. Shell and pearl were imported for the production of buttons, with so much waste shell produced by the process that pits were dug in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter to bury it. Many buildings today are said to have their foundations built on mother of pearl.

The button trade is one in which the development of assembly line processes and division of labour developed. In the 18th century, it was calculated that each button would pass through fifty pairs of hands, with each individual worker handling up to 1,000 buttons per day. By 1865 machines began to be introduced into the button trade, with the number of workers employed reducing to around 6,000 compared with about 17,000 in 1830, with a large number of women employed. Even after mechanisation was introduced, it took around 14 workers to put together a single button.

Buttons were attached to a piece of card, fourteen buttons on each card, with one worker capable of sewing 3,600 buttons onto cards in one day. Pearl buttons, because of their frailty, continued to be made entirely by hand.

Birmingham led innovation in the button trade; between 1770 – 1800, 21 patents were granted for improvements in the fastening of clothes, with 19 originating in Birmingham, including flexible shanks, and fancy silk, and porcelain buttons.

James Grove & Sons Horn Buttons

Perhaps the most famous button company in Birmingham, and the longest running, James Grove & Sons was established in 1857 by James Grove, previously apprentice to another leading button maker Thomas Harris. James Grove specialised in uniform buttons, supplying the Ministry of Defence, Post Office, police, railways and both the Confederates and Yankees during the American Civil War (although neither side ever paid). At its height, when every button was made by hand, the firm employed around 600 people, but sadly went into receivership in 2012.

A new Birmingham-based company, Grove Pattern Buttons, was founded in the Jewellery Quarter by an entrepreneur who spotted James Grove & Sons pattern books and dies being sold online following their closure. Unfortunately Grove Pattern Buttons also appears to have closed down.

A number of writers wrote contemporary accounts of the Birmingham button industry, including Charles Dickens, and The Penny Magazine (including illustrations). The Coat Route by Meg Luken Noonan includes a chapter profiling James Grove and Sons. A large number of children were employed in the buttons trade; this website contains records of inspection of their working conditions carried out in the 1800s.

NOW: I don’t believe there are currently any Birmingham-based buttons manufacturers, although vintage buttons are widely available on ebay. A Jewellery Quarter building, dating from 1824, which originally housed William Elliott’s button factory (which specialised in a silk-covered button William Elliott patented) has just reopened as a restaurant and bar called The Button Factory.

UPDATED: Rachel updated me that George Hook, based in Smethwick, whose family have been involved in the trade since 1824, produces pearl buttons and gives talks about pearl button making.

Thimbles

Another item produced by Birmingham’s “toy” and jewellery industries were thimbles. Initially produced in brass, silver thimbles began to be widely produced in Birmingham following the founding of the Birmingham Assay Office in 1773; founded with the support of industrialist Matthew Boulton, to prevent silver items having to be sent to London for taxing.

In 1769 Richard Ford of Birmingham patented a process known as ‘deep drawing’, which was taken up by thimble manufacturers. Instead of casting in a mould, the process forms the thimble shape from a sheet-metal disc. The process needed less skilled labour, was faster and used less metal.

NOW: I believe thimbles are still being produced in Birmingham’s Jewellery Quarter, and vintage thimbles are widely available on ebay.

P.S. I maintain a list of current British fabric and haberdashery manufacturers, here.